The first post on Kylerec is here, so if you haven’t been keeping up with these posts, you might want to start there. This is also the last post on the Kylerec 2017 workshop, which has been fun and rewarding to write about (with some much appreciated help from Agustín Moreno)!

If you’re following along with the lecture notes from Kylerec, then this post corresponds to Day 4 (Talks 11-14), consisting of the following four talks:

- My talk following sections 2-3 of Hutchings and Taubes Introduction to the Seiberg-Witten equations.

- Jie Min’s talk, on section 4 of those notes (the symplectic manifold case), but also continuing on to Morgan and Szabó’s paper which can be used to classify homotopy K3 surfaces

- Tom Gannon’s talk on fillings of unit contangent bundles, following Li-Mak-Yasui and Sivek–Van Horn-Morris

- Dani Álvarez-Gavela’s talk on how Lisca and Matić distinguish contact structures using Seiberg-Witten theory

A pre-introduction to Seiberg-Witten theory

The Seiberg-Witten equations have been discussed in this blog by Laura Starkston in a sequence of four posts. For more information, details, and clarification, the interested reader should go there, or to the notes of Hutchings and Taubes mentioned in the introduction to this post. I call this a pre-introduction because the details will be rather sketchy. I will not even write the Seiberg-Witten equations down. The reader interested in skipping to fillings may wish to jump ahead to the two-sentence summary at the end of this section.

I should mention that the Seiberg-Witten equations arise naturally in physics, although I’ve not yet personally taken the time to understand Witten’s motivation for first writing down these equations, which he called the monopole equations. If you are interested in that sort of thing, maybe check out this MathOverflow post.

Consider a closed oriented smooth 4-manifold , together with the following data:

- a Riemannian metric

- a self-dual 2-form

(meaning

where

is the Hodge star with respect to

)

- a

-structure

You might be asking – what’s a -structure? Recall that for

, one has

, so one can form the connected double cover

. Then one defines the Lie group

This comes with a map to with fiber

. The metric

yields a principal

-bundle called the frame bundle, which topologically doesn’t depend on the metric, and a

-structure is just a principal

-bundle such that quotienting by the

-action (sitting inside the

-action) recovers the frame bundle.

For oriented, which is the case of interest to us, the space of

-structures,

, is an affine space modelled on

(this is not obvious). Also in the 4-dimensional case, representation theory of the Lie group

yields two complex 2-dimensional spinor bundles

and a complex line bundle

. The Seiberg-Witten equations are then equations on pairs

consisting of a

-connection on

and a positive spinor (a section of

). We write this simply as

.

Let be the solutions to this eqution. There is an action of the gauge group

(given by

). This action is free except for reducible solutions where

, in which case the stabilizer is

. The quotient yields the moduli space (where we suppress

from the notation):

Theorem (key, nontrivial): The space is always compact.

Let be the rank of the positive-definite part of

with respect to the intersection product. We will assume

. This implies that generically paths of choices

for a fixed

will avoid reducible solutions, yielding the following.

Theorem (standard Fredholm theory): Consider with

and some fixed

. Then generically (with respect to

),

is a smooth finite-dimensional manifold of dimension given by topological data (only depending on

and

)

can be given an orientation with some auxiliary topological choice (not depending on

)

is a cobordism invariant

Definition: For , and for

with

, we define the Seiberg-Witten invariant

, where we count

with signs according to the auxiliary topological choice.

One can also define the Seiberg-Witten invariant when the dimension is positive, but there is the simple type conjecture that in such cases, this invariant is zero. In the case of symplectic manifolds, which is the case we care about, this is known to be true (by Taubes). By construction, the Seiberg-Witten invariants are diffeomorphism invariants (once we have fixed our auxiliary data for determining an orientation of ).

We are interested in the case of symplectic manifolds. In this case, there is a canonical choice for the data which orients the moduli spaces of solutions to the Seiberg-Witten equations. There is a natural morphism given by the

where

is the line bundle mentioned before. (This is not an isomorphism if

has 2-torsion.)

Definition: A class is basic if there is a

-structure

with

such that

.

We finish by stating the following facts without proof (although we did discuss the proofs at Kylerec).

Theorem [Taubes]: For a symplectic manifold, are basic classes (with Seiberg-Witten invariants

).

Theorem [Corollary of the same Taubes paper]: When is minimal, Kähler, and of general type (the last condition meaning

and

), then

are the only basic classes.

Theorem [Corollary of Morgan-Szabó]: If has

,

, and

, then it is a rational homology K3 surface.

SUMMARY OF THIS SECTION: The Seiberg-Witten invariants form a diffeomorphism invariant, hence so do basic cohomology classes. This fact, plus the previous three theorems, are all we need.

Filling unit cotangent bundles

Unit cotangent bundles, which we shall notate as , have canonical Weinstein fillings given by the unit disk cotangent bundles. It is a natural question to ask if this natural filling is in fact the only one up to some notion of equivalence. We shall restrict ourselves in this discussion to when the base space is a closed orientable surface

of genus

. We mostly focus on the

case, but we quickly review the case of

.

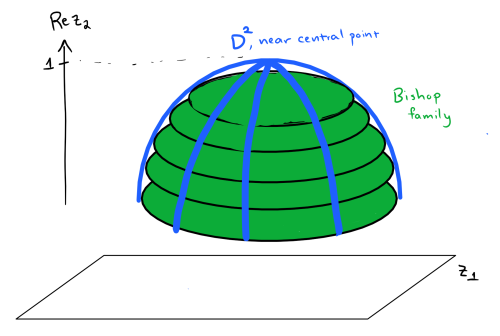

Let us begin with . In the first post on J-holomorphic curves, when discussing McDuff’s classification result, I mentioned that

has a unique minimal strong filling up to diffeomorphism. Further, Hind proved that Stein fillings are unique up to Stein homotopy.

For , in the second post on J-holomorphic curves, when discussing Wendl’s J-holomorphic foliations, I mentioned that every minimal strong filling of

to the standard one. In fact, he proves further that every minimal strong filling is symplectically deformation equivalent, which is a little stronger. Also, Stipsicz proved that all Stein fillings are homeomorphic (to

).

To summarize roughly (though we know a little more), for , exact fillings (which are automatically minimal) are unique up to symplectic deformation equivalence.

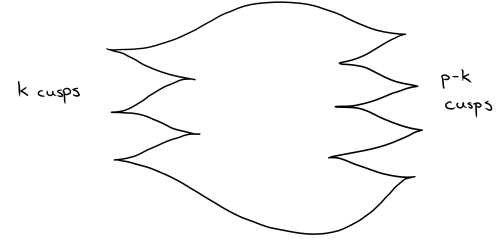

So now we move on to . We focus on exact fillings because strong fillings (even minimal ones) are too weak to get a handle on. One can build strong fillings with arbitrarily large positive second Betti number

. This involves cutting out a cap (with concave boundary) from one particular strong filling (McDuff) and gluing in other caps with higher

(Etnyre and Honda).

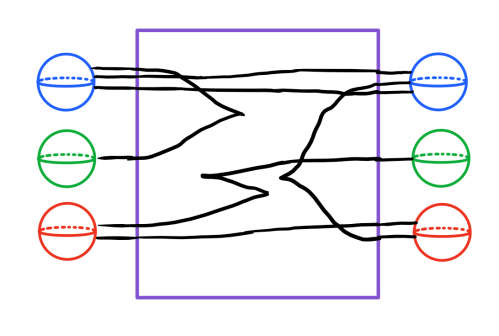

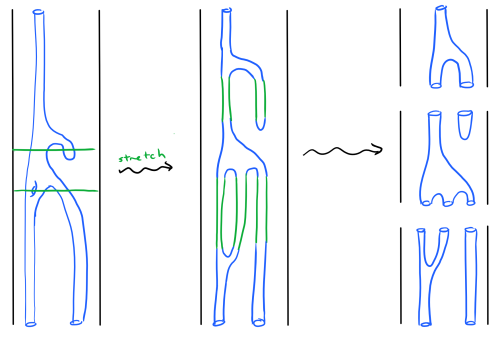

The idea, in this paper of Li, Mak, and Yasui, is similar to the idea we encountered in McDuff’s approach to the (and more generally

) case – attach a cap, and then use classification results to figure out what you had in the first place. The following definition is the correct version of cap that we need.

Definition: A Calabi-Yau cap for a contact 3-manifold is a strong cap (like a filling, but with a concave end instead)

with

torsion.

Theorem 1 [LMY]: If a Calabi-Yau cap exists for , then the set of triples of Betti numbers

is finite as

ranges over all exact fillings.

Remark: This theorem is not true if instead we let range over all strong fillings. This was noted above when we remarked that

could be arbitrarily large for a strong filling.

Theorem 2 [LMY]: In the case of the unit cotangent bundle, then for any exact filling , its homology

and intersection form

are the same as that of the standard filling.

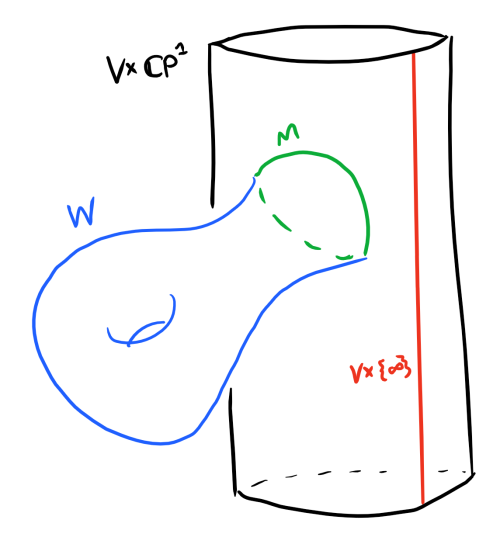

Sketch Proof of Theorem 1: Some messing around with Chern classes tells us that if we have an exact filling and a Calabi-Yau cap

for

, then the glued manifold

satisfies

. Then one can plug this into classification theorems by an invariant called the symplectic Kodaira dimension

. In the case when

is minimal with

, we must have

. In this case, when

, then the Morgan-Szabó result mentioned in the Seiberg-Witten section implies that we have a rational K3 surface, hence we know its Betti numbers. Tian-Jun Li extended this result to a classification for

and

minimal but with arbitrary

. Otherwise, if

is not minimal, it must have

, and one needs to be a little more careful, working with a symplectic surface in

to which an adjunction inequality ends up bounded the Betti numbers.

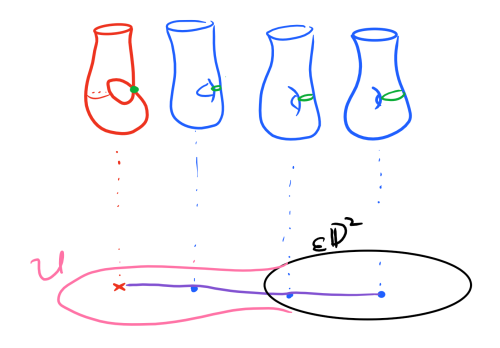

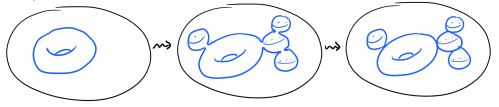

Sketch Proof of Theorem 2: The key lemma is to construct a symplectic K3 surface with

non-intersecting Lagrangian tori in the same homology class which all intersect a Lagrangian sphere transversely in one point. Then we can perform Lagrangian surgery to give an embedded Lagrangian genus

surface

. Then

is a Calabi-Yau cap for

. Playing around with intersection forms, we see that attaching this cap must yield a rational K3 surface (one can rule out all other possibilities given by the classification theorems mentioned in the proof of Theorem 1), from which playing around more with exact sequences of homology and intersection forms gives the result.

Remark: The classification-type results with respect to symplectic Kodaira dimension are the only place in this section where Seiberg-Witten equations enter the picture, and are really the meat of the argument, in some sense. The rest just comes from exact sequences and understanding intersection forms, which is comparatively simple, staying far away from gauge theory.

The main theorem of Sivek and Van Horn-Morris is the following:

Theorem [SV]: Weinstein fillings of are unique up to s-cobordism rel boundary.

If you’re worried about the word “s-cobordism,” just think of this as a beefed up version of homotopy equivalence that comes relatively easily in this case once we prove the homotopy type of the filling is unique (is a ). There are some beautiful group-theoretic arguments which go into this argument, but we have essentially already seen how the Seiberg-Witten invariants come into play, so I won’t include a sketch of the proof.

Finally, I mention a little bit of history with regards to these two papers, because I was confused looking at the most recent versions as I was writing this, not for lack of improper attributions, just by my own confusions about reading them concurrently. The theorems stated are quite similar, as are aspects of the proofs, despite them being stumbled upon independently. To clarify, Theorem 2 of LMY did not exist in version 1 of their paper. About a year later, within a month of each other, SV posted their paper and LMY posted version 2 of their paper. Independently, SV had proved some subset of Theorem 2 (with some small fudge factor in and the intersection form) while LMY had proved the full version. SV’s result was good enough for them to prove the s-cobordism statement, and as far as I can tell, version 2 of SV is just version 1 but where they mention that they have learned that LMY proved the strong version of Theorem 2.

Homotopic tight contact structures which are different

The main theorem, due to Lisca and Matić, is the following:

Theorem [LM]: For any , there exists a rational homology 3-sphere with at least

distinct contact structures up to contactomorphism which are homotopic as plane fields.

In this short section, we simply sketch the proof.

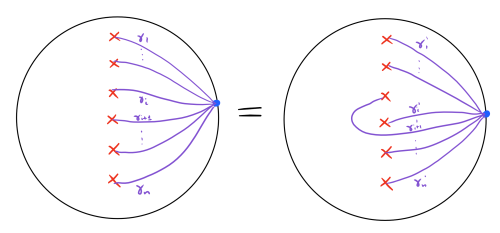

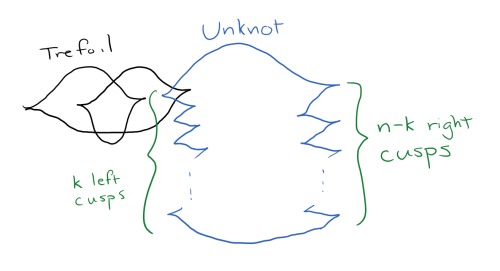

Sketch of proof: One must begin by simply writing the Gompf surgery diagrams (described in the post on Weinstein fillings) for the contact structures in question. One has that a rational homology sphere can be obtained by 0-surgery on a trefoil and -surgery on an unknot which links with the trefoil once, and so suggests the following surgery diagrams so that the canonical framing on the Legendrians drawn below gives exactly what we want.

We denote these contact structures by for

. We will show that for a fixed

, all of these are homotopic but not contactomorphic. One computes via results of Eliashberg that for the corresponding Weinstein fillings

(which are diffeomorphic) that

, where

is the class in

given by the handle coming from the trefoil in the surgery. We shall call the smooth underlying manifold

.

The homotopic part is rather simple. By classical results (clutching functions, and computing Pontrjagin classes to plug into the Hirzebruch signature theorem) following an argument attributed to Gompf, one can show that the homotopic result can be reduced to proving that , which is itself clear since

.

As for the contactomorphism part, one embeds into a minimal compact Kähler surface

of general type and

. This is a nontrivial statement, but is nonetheless true. In fact, because

and

have isomorphic collars, one can attach the same cap to produce Kähler surfaces

and

. One can extend the identity on these caps to an orientation preserving diffeomorphism

acting by

on

(by work of Gompf). But also, since we have a minimal compact Kähler manifold, by the theorem mentioned in the first section as a corollary of Taubes’ work, one has that

is a diffeomorphism invariant, and so we see that

. So these must restrict to the same thing on

, where we showed

. Hence,

, so either

or

. Thus, increasing

, we can find arbitrarily many homotopic but non-contactomorphic contact structures.